Elfriede Bennett, one of my moms and my biggest fan, passed on to her heavenly reward, Wednesday, October 15, 2008, sixty-one years to the day after she was married to Bob Bennett, a soldier and musician that she met in Germany. The story of their struggle to get married, The Color of Love, is a statement to strength of the union of their souls, as one for fifty-one years before Bob's death in September, 1998.

Friede approached me in 2004 to write her story. Here 'tis.

Little did I know when I went to work at the U.S. Army Air Base several miles from my hometown of Offenbach/Main on December 4, 1945, that my life was about become full of such joy, but at the cost of much heartache. As a stenographer/secretary to the base adjutant and base interpreter, I greeted a sergeant who was requesting to speak to the base commander. He came to report an ambulance accident that he was in while traveling with several officers off post and his limp and use of a cane gave away his injuries.

It was at the base dispensary that I saw the same sergeant the following day. Over the next few days, our paths crossed and our small talk began, with me revealing that I traveled by bicycle ten long miles each day to the job. He offered me some transportation in my direction and I accepted.

I was really happy to meet Bob Bennett, a well-spoken and charming Black American from Boston, Massachusetts, and we became very attached to each other. However, if there was a written taboo concerning associations with Black soldiers on an American base, I was totally unaware of it. In 1946, The U.S. Army was not quite at the end of its policy of segregating troops by skin color, except that the unit’s officers were White.

When Bob and I became noticeably a pair, my new job assignment became the kitchen, for cooking detail. The fall from the grace of secretary to cook was too much for me to handle, so I quit the base.

At the same time, Bob, was a part of the unit being reassigned to an air base in Southern Germany. Since a good friend was making the move with the unit also, Bob and I decided to get married and I would follow along to live in the town near the new base. Boy, did all hell break loose with that move!

Before our wedding occurred, the pregnancy did, and our plans to marry were met with a refusal from German authorities. The local mayor was getting his orders not to marry us from the base commander. Bob, my fiancé, was facing a dismissal from his unit and a return to the U.S. to face the music of race mixing, which was a clearly defined prohibition of American and Army culture.

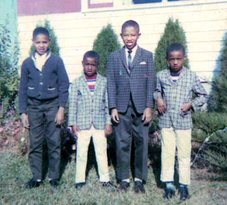

Our son, Dwayne, was born on February 5, 1947. It would have normally been a day of unforgettable joy for most mothers in the world, however the base commander gave personal orders for me “not to bring the baby out in the street or I will send you back to Russia.” Since I’ve never been to Russia, I thought that was some pretty strong talk for a person who had no authority over a German citizen. But still, the commander was a vocal obstacle in the path to our marriage and our family.

The racist commander fabricated charges and allegations against Bob, but he defended himself against the threats of jail and transfer/deportment back to the States. Bob lost his court martial on trumped charges and was restricted to his quarters. The power mad commander was forcing me into action.

One of Bob’s friends was positioned to leak to me that he had seen transfer orders scheduled for the next day. I began walking to Erlangen, Germany, home to the Eighth Air Force Command and two days later, I arrived early to see if Colonel Martin would have an audience with a German civilian.

I was admitted to the colonel’s office and found that he was not only aware of the request that Sergeant Bennett had put in to marry a German, he was in agreement with the papers. He proved to be on our side by calling the base in Roth, talking with the commander and ordering Bob’s release from detention. He arranged transportation for me back to my home and child, following me to Roth the next day to investigate the whole terrible affair.

Bob wasn’t idle during these ugly days; he had written a letter to General Dwight Eisenhower, mailed it to his sister in Massachusetts and she forward the letter to a congressman. The power of my companion’s words must have compelled the general, because Eisenhower responded with not only an approval of the marriage request but a choice of dates for the ceremony. With his help, we chose October 15, 1947.

Base Commander Glass promptly transferred Sergeant Bennett to Rhein-Main and took a parting shot with an AWOL charge for lateness. Bob fought the AWOL battle and subsequent loss of his sergeants stripe, but we had won the war to liberate our rights to marry.

The marriage, by law, was by the Mayor of Roth, Germany, with close friends and my family at the Enlisted Men’s Club. The next day’s icy marriage proceedings by American officials freed us to escape back to Frankfurt, gladly fleeing the hideous restrictions of the U.S. Army hierarchy there in Roth. We encountered harassment from military police as we arrived at the train station, “No fraternization between Black soldiers and German Fraeuleins!” “Kiss off, boys. We got a license.” MPs were left in disbelief.

When your marriage is to someone from a country with a tradition of racial segregation, the problems are seemingly endless. Bob was due for a transfer Stateside a month after our marriage, but there were military regulations disallowing me and Dwayne to travel with him. I had to wait another month and during that time I found the two of us to be people without a country.

To German authorities, I was married to an American and no longer eligible for German food rations. But to the Americans, I was German, thus ineligible to shop at the Post Exchange or Commissary. Thank God, not for government officials but for friends who helped our survival.

Two week after Bob’s departure we finally were passengers on December 18, 1947, boarding the U.S. Army Troop Transport General Callan and heading towards the English Channel to pass the ‘White Cliffs of Dover.’ Us passengers watched sunshine on the cliffs and, truly, they shown white.

After the General Callan stopped for passengers in Dover, we set course for the Azores and just in time for christmas, the crew and passengers were greeted with the suddenness of a hot and heavy storm. We weathered the rough seas and sailed onwards to the United States of America.

If the seas weren’t rough enough, the hatred was from my fellow sailors, the military people. An officer order me off the upper deck with a threat that leaving my stateroom could cancel my disembarkation in New York. and blind hatred that we encountered. But time has healed and made me very grateful for our sizable family, which includes five children, five grandchildren and several great grandchildren. Our fruitful love, that has been undefeatable from that chance meeting in December, 1945, has multiplied Black soldiers, who had heard the grapevine news about the Bennett Family’s victory over injustice, came to Little Dwayne and my aide with clean clothes and I was allowed out of the stateroom but to go get food for the two of us.

How excited everyone was to see the Statue of Liberty coming into view on the port side of the troop ship; welcoming us in the bright sunshine with her book and right hand extended. To this day, it was a sight never to be forgotten; a proud lady saying “Welcome, all of you, to this great country.”

Of course, despite what the statue was declaring; restrictive military agents wouldn’t allow me to get help with my baggage and baby. But despite the formidable odds and obstacles to our resolve, we made it.

Bob picked us up at Fort Hamilton and took me to his sister’s in Massachusetts. But we couldn’t be too comfortable together for long because the Air Force had a transfer in assignment for him to Salinas, Kansas. And that transfer didn’t include his young family, so he quickly lobbied to transfer to a post that would accept families.

No help came from the post’s chaplain, “I didn’t tell you to marry her!”, he blamed. With the help of a colonel in Boston and his connections in Washington, D.C., Bob’s transfer was to Lockbourne Airbase in Columbus, OH. We arrived in early 1948 and by early 1949, Sergeant Bennett became a civilian, along with his family.

Race problems awaited us in civilian life; I lost a job when I was spotted by fellow workers being dropped off in front of the office by my husband. But he WAS my husband and that WAS what husbands do for working wives. The loss of a job wasn’t something that I couldn’t take; my husband was a great man, whatever his skin tone.

Paper and written words about the experience of our time during those awfully struggling years can’t cover all of the indignities; emotional turmoil over nearly fifty-one years together.

We were able to retire, look back on our accomplishments, our happy family and enduring love. And how many couple think of General Eisenhower on their wedding anniversary day? Without his compassion and approving support of our marriage, what would have happened to our lives?

Of course, losing Bob to his illness in September of 1998, has triggered an unbearable shock that our great times together will not continue. What helps me, though, are all the good memories and all the love from our immediate family.

I just wish that our good life together could have gone on and on and on...

Rest in peace, Friede, with continuing love from your decendants.

No comments:

Post a Comment