Delores Grettavon Williams

Delores Grettavon Williams was born in Amonate, Virginia to

Myrtle Hairston (April 7, 1916-November 4, 1979) and

Robert F. Williams (March 1, 1913-August 25, 2005). Robert was a coal miner from Gary West Virginia, who had gone to Amonate because the coal mines in Gary had closed temporarily because of the Depression.

Robert was nineteen and Myrtle, sixteen, they got together and soon she became pregnant. It soon became evident that Myrtle didn’t have motherly instincts and she only stayed married for less than three years. It is said that her mother,

Janie Moore Hairston had Myrtle sterilized afterwards, but the date of that trauma is unknown.

So with Myrtle unwilling to be a mother, the responsiblity was lovingly undertaken by Robert. His own mother,

Fannie Mae Hairston Williams, had passed away in 1928 and Robert lived with his father,

George Williams. He moved back to Gary, West Virginia to work in those mines.

Robert said that Delores was a happy child and like him, loved the same Gary schools that he had gone to. Soon World War Two interrupted the family and Robert was drafted into the U.S. Navy in 1943. Delores was sent to Amonate and while Myrtle enlisted in the U.S. Army, she lived with

John and

Nannie Mae Hairston, Myrtle’s younger brother, who called her

Prellie.

Delores was a young, bright college student, entering Bluefield State Teachers College in 1949 at aged sixteen. Her roomate was

Josephine Griffin, who later married her college sweetheart,

Otto Charles.

She got together with

George Howard, a chemistry major from Walnut Cove, North Carolina, who graduated in 1950 and they married February 25, 1950. Their son,

Arnett (me), was born September 6, 1950 in Welch, West Virginia, near his mother’s coal mining hometown, Gary.

At 2:00 a.m., that morning George with his friend,

Arthur Froe driving, took his young wife from their home in the coal fields of Gary and their destination was Stevens Clinic, in Welsh, West Virginia, six miles away. “Your father came back from the hospital and said ‘It’s a boy!’” Robert remembered. Delores was like all young moms, enjoying the great feeling of the gift of a child.

She started a babybook in late November, 1950 and among her first remarks were “Baby was nice size; not too small or too large, but very ugly. I sure hope he improves. He’s an exact replica of his father. Even to that head.”

She added remarks, “Most people said that my baby was ugly and I readily agree, but he’s going to grow into a beautiful baby with Mommy and Daddy’s help.”

She took me for my first photo shoot to the Welch Photo Store on February 17, 1951 at five months of age. She happily wrote, “Baby is eager and easy to photograph and his looks have greatly changed.”

She notes in the baby book, “Arnett always has been an easy baby to handle; very seldom cross and easy to love. At six months he hated to sit down, loved to stand and try to walk. He is as devilish as anything. When he was five months old, he cried after his daddy, at six months he stood alone in the bath tub. He’s a very frisky baby. At night he likes to wake up and play after everyone else in the house is asleep, especially me.”

After several auto trips to Amonate, Bluefield, Walnut Cove and Martinsville, Virginia to visit my father’s family, Mom took me on my first train trip when the family resettled to Columbus, Ohio. After nearly two years in Columbus, Dad got a job at the Westinghouse Appliance Plant as an industrial chemist.

The earliest remembrance that I have, at aged three or four in 1955, is walking back home from a car buying trip. We lived at 175 North Chicago Avenue and I remember crossing West Broad Street. We had purchased a 1951 Oldsmobile and walked back home before taking delivery of it. I can recall driving to White Castle at Central Avenue and West Broad Street and enjoying those wonderful little burgers that cost a dime and carryouts were served by carhops who were dressed in uniforms.

There was a family named

Harris who took up residence next to us on Chicago Avenue and they had a daughter,

Connie, who shared the same birthday as me, September 6, 1950. So our mothers threw a party for us on that day in 1956 in our backyard. Delores was twenty-three.

When I was eight and my brother

Gerald was six, we were given a Christmas gift of ice skates. Mom took us to Franklin Park in Columbus’ Eastside for two seasons of skating and I recall the three of us skating on the frozen pond and my little ankles getting scraped from the chafing of the shoe skates, but we enjoyed it.

When we were children we belonged to a neighborhood/street club that met each Saturday at

Mrs. Booker’s home up the street on Chicago Avenue, near Cable St. On those days we would play, get education, games and go to Franklin Park for picnics. Mrs. Booker, an older woman, had an unpowered sewing machine and we would kick the pedals that made the needles work.

We were friends with

The Washingtons from across the street and

The McKeevers who had nine children. We called Mr. and Mrs. Washington

Mom and Pop, because they were our great-grandparent’s age. I can still see Pop Washington stroking the leather belt that he used to keep his razor sharp and I can hear Mom Washington’s voice as clear as it was yesterday.

Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Nowles lived across the street also and had a double sized yard where they raised chickens. Their son was named

Teddy and his son was a dwarf named

T.J. who was my age and later played football at Columbus Central High School.

The family was friends with other Chicago Avenue families;

The Buckners, the Evans, the Roberts and

The Flemisters. We would go down the street to Mr. Flemister’s because he had a pair of electric hair clippers and we would go for hair cuts. We’d get a group together for hair trimming day and those clipper surely got hot after a couple of heads.

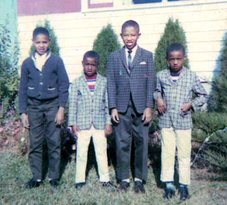

Gerald was born June 22, 1952 and the twins,

Keith and

Kevin, were born September 17, 1955. In 1958 or so, Mom began working at the General Motors plant on Columbus’ westside, just down the street from Westinghouse were Dad worked. She worked there less than two years.

The first Church our family became aligned with in Columbus was St. Paul A.M.E. on Long Street. My father went to a barbershop that was right next door and his barber and later mine, was a Baptist minister named

Benny Brogsdale. Grooming rituals of Negro men included shaves complete with steaming towels wrapped around the face and tweezers with barbed ends to lift the curly ingrown hairs from the skin and neck.

I also have first memories of accompanying Mom to the beauty shop on Mount Vernon Avenue, the heartbeat of Columbus’s Negro business during the mid 1950s. I have recollections of women, gossip, hot steel combs resting over flames and the aromatic bouquet of smoldering hair being styled; the decorous rituals of African women through the ages.

I entered Chicago Avenue School on September 11, 1955 at the age of five, became a kindergarten student and my first teacher was

Nina Bowen. As a first grader I remember a fellow student,

Jo Ellen Valentino, because she was a good singer; her favorite song was

Tammy’s in Love. I recalled getting spanked by Mrs. Wolske as a third grader for being a smarty because I went home and got spanked again.

Punishment was memorable as a child because we got whipped with a variety of things. We dropped Kevin off the Harris’ porch, onto his head and Mom told me to go get a switch. Kevin fell again under the outdoor swing and I got beaten with the bad end of a garden hose. Mom suffered under the strain of four over-active sons.

When I was six or seven, a Christmas gift for Gerald and I were ice skates. Mom took us to Franklin Park several times during cold winters to try them out; she had a pair also. I remember getting scrapes on my ankles from skin chafing against skate leather, but I have a vivid picture of being on ice with my mom.

I was eight years old in January,1959, in the third grade at Chicago Avenue School, when the westside levee broke and the flood waters came. I remember my father, George, climbing into the crawl space above our ceiling about bed time and turning off the pilot light to our gas furnace. Our parents gave us the sense that we were in an emergency but were not panicked. All four Howard Boys crawled into bed together and body heat kept us warm.

Within a few hours, we were awakened and it was time to evacuate; the Ohio National Guard troop transporter was parked in our flooded street and military men were carrying neighbors in porch chairs to the covered military truck. Our first stop was Fire Engine House Number Ten on West Broad Street and from there, our family was shuttled to the Navy/Marine Recruiting Center located on Sandusky Street at Dublin Road, in the same site that now stands Confluence Park Restaurant.

I recall hundreds of people overnighting there on wooden and canvas folding cots. After breakfast, ten hours since we were evacuated in the middle of the January night, we contacted our family friends, Otto and Josephine Charles, who had an apartment on Clifton Avenue in East Columbus and spent several days with them, before returning back to the westside. Josephine was Mom’s roomate at Bluefield State Teachers College.

Flood waters had crept up to our front steps, but no closer and since we had no basement at 175 Chicago Avenue, we saw no flood damage. But our family purchased acreage in Plain City/Union County, built a new home and by November, 1959, we had fled the Bottoms and flooding for good.

In the summer of 1959 George began building a new residence. I think that Mom was still working at General Motors when the house building began, but I remember the meals that she used to fix and the picnic baskets that we’d take to Plain City on Sundays to work on the house.

Chicken dinners, complete with fixings and delicious fresh rolls that were oh-so sweet and wonderful were the fair that we’d dine on. Mom had a magic in the kitchen and when we finally moved on November 9, 1959, my folks grew a garden and Mom canned cherries, strawberries, apples, green beans, corn and tomatoes, among other items that we grew.

The Howard’s and their four boys moved into 8564 Frazier Road, next door to

The Thomas Crumps and their four girls, who had preceded our move by one month. Frazier Estates was to grow into a neighborhood of twenty- four homes occupied by African-American families.

Although the Frazier kids were five miles from Dublin local schools, we were bussed six miles to Plain City Elementary another five miles to Jonathan Alder High School. Plain City was a culturally diverse community; a large population of Old Order Amish, Mennonites, a number of long time and respected black families made up the local population of 2400 people.

Snapping beans, shucking corn and peas became as much a ritual as playing baseball. In the basement we had a wringer washer and twin sinks that Mom taught us how to use when I was aged ten. We fill the washer with a short hose that ran from the sink and the washer emptied via a hose from the bottom into the sump drain in the floor. We’d use the two sinks to rinse our clothes, then we’d take the clean clothes out to the line to dry.

After they were dried, then we’d bring them in and she’d show us the process of setting up the board and firing up the iron to press the fresh clothes. I thank Mom for showing me how to press a dress shirt and put a crease in my pants.

I remember the day that Mom rented the trailer for her 1955 Chevy and brought home the piano. She backed into the driveway, we unloaded the huge instrument and wheeled it into our recreation room. Eight little hands started pressing keys and within the first hour I had created a blues melody.

It took a year for Gerald and I to get through Teaching Little Fingers To Play and while we were learning, Mom was teaching her fingers too. We had just started Book Two when Mom ceased our lessons, apparently frustrated that our exploding passion for little league baseball was destroying her investment in our training. It was the first signs of a depression.

The Howard house soon became a magnet for musical instruments; a bugle from

Billy Leftwich, a guitar and field drum from

Uncle Al Turner in Twinsburg Heights, Ohio. Mom also had acquired a monophonic, reel tape recorder and she recorded television programs. One of the things that she recorded was the New York Philharmonic Orchestra playing

George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. This has become one of my favorite symphonic pieces and I have several recordings of it.

Mom and Dad had a bag of pictures of them when they were younger. I can remember snapshots of Dad in the Army when he was stationed in New Guinea when it was so hot that the soldiers were shirtless annd dressed in shorts. I recalled college photos from Bluefield State when George had several of his girlfriends, including Mom, draped over him and in the late model Buicks. We have lost those photos.

I remember a violent wind and rainstorm, perhaps it was even a tornado in the area in the early 1960s. The winds blew so that the rains were coming in the back door and Mom held onto that door throughout the rain.

Beginning in 1960, our church home was Allen Chapel A.M.E. in Marysville, where

Reverend Thomas Liggins presided. Their new religious home was named after

Bishop Richard Allen, organizer of America’s first African American church in 1803. The Allen Chapel community built their first church in Marysville, Ohio, in 1879 and Howard family joined

The Flemings, The Browns, The Carters, The Evans, The Calloways, The Woodsons, Vada Beauchamp, The Barnes, The Martins, The Leftwitchs, The Estis and they became a regular in attendance. George served as Sunday School Superintendent most of his church life.

Mom sang in the choir and she would take solos,

Lead Me, Guide Me, When I’ve Gone the Last Mile of the Way. She was an excellent singer and good church woman.

It was through our church that we got a number of musicial instruments from

Mrs. Cornetta Palmer. Her husband,

Pete, had been a drummer during the 1930s and one day we cleaned out her attic and took home a bass drum, cymbals, a Chinese tom tom, a xylophone and various other noise makers. There was a scene painted on the head of the drum and a light blub inside, but we couldn’t wait to paint over it. That was a mistake, because that scene of some exotic painting was valuable.

Mary Liggins-Goodrich was the wife of Tom Liggins, pastor at both Allen Chapel A.M.E. in Marysville and Zion A.M.E. in Delaware, OH. The Liggins’ had four children right around our same age,

Tommy, Timmy, Teresa and

Tony. She was also our piano teacher and Mom’s best friend.

Mary was so close to Delores that she calls me her “son.” She said that they would see each other at church on Sundays and enjoy each other in the kitchen. “Couple of things that stayed in my mind, was, a lot of times we would go to each others houses for Sunday dinners. Your mom made the best fresh lemonade and delicious fresh corn, picked from her garden; pot roast and green beans, also picked from the garden. Her cooking was awesome, although she liked my dinners as well, she loved my pound cakes. We often talked about her lemonade and my pound cake.

Tom recalls being in school when he met Mom. “I had five kids, two churches, worked at the Post Office and went to seminary at Wilberforce University in the evening; talk about having a full plate. Delores would read the textbooks that I was assigned and give me a synopsis of what I should know to pass my courses. She was an avid reader and had an analytical mind, which I admired very much.”

One Sunday in 1962, Mom invited

Robert Duncan, a Republican lawyer and soon-to-be Federal Court judge, to Allen Chapel to speak.

James A. Rhodes was running for his first term as Ohio governor, Mom and Judge Duncan campaigned for Rhodes and likely met during those campaign days.

“Your mother was chair person for it and did a fantastic job,” says Mary Liggins-Goodrich. “She sent me a thank you note, thanking me and teasing, saying that me and Mrs. Palmer were "green hornets" in the kitchen because we've never served kitchen duty before. I always played the piano and Mrs. Palmer ushered. Your mom was the one who did things in the kitchen for dinners, etc.”

But they all suspected Delores’ growing depression. Mary says, “In our conversations Delores would tell me that she was tired of the garden, country life and she wanted to move back to the city. Tom says that Delores would go into a room and shut herself off from family.

George and Delores visited The Liggins Family in Delaware the Saturday prior to Palm Sunday, April 6, 1963. They enjoyed the womens cooking and Delores’ lemonade, but the next morning, when George drove the church bus, Delores stayed home.

My mother, Delores, who planted of the seeds of music in her four boys died the next morning, Sunday, April 7, 1963. When we return home from Sunday services at Allen Chapel, my brothers Kevin and Gerald raised the garage door and saw mom’s arms dangling out of the door of her Chevy parked inside. She had stayed home from church many mornings during the previous months, suffering from the depression that we children knew little about. Her self-asphyxiation was the end of a difficult time for her.

Reverend Liggins said that he got a call from George that Sunday afternoon. “Can you come to Riverside Hospital? Something has happened to Delores.” Tom said that he got a sinking feeling in his gut that wasn’t good. Mary said that the gravel flew as he left the home in Delaware alone in a rush.

Tom Liggins’ memory is fresh, “Mary and I were devastated, helpless, in shock, crying. What could we have done to help her? What a thing to happen so young in a ministry?”

After the ambulance had left for Riverside Hospital, we boys went over to

Karlton Williamson’s to play basketball and our games were interupted when we got a call across the lawn to come home. Our father was weeping when he told Gerald and I that our mother was gone. I immediately broke down, hugged him around the neck and said, “It’s alright, Dad. We’re gonna’ make it.” He called my grandad, Robert, and he came later that evening from Charleston, West VA.

Delores’ funeral services were handled by the Faulkner Funeral Home in Marysville, where the wake was on Tuesday, following the Sunday passing. The funeral was on Wednesday at the Allen Chapel A.M.E. and among the very long list of all of our family and friends who came to Marysville, in addition to my grandfather was Delores’ mother,

Myrtle Scales, who was living in Denver, Colorado. We picked her up from the airport Tuesday evening, she slept in our parents bedroom and we smothered her with our curiousity.

Myrtle wore a beautiful green dress and a large hat to the funeral and I remember her weeping. But I can remember little else. We took her back to the airport the next day and never heard from her again. Delores died on Myrtle’s forty-seventh birthday.

Delores, it seems, was a victim of codependency; the destructive behaviors that result from a youthful abuse that has not been properly addressed in adulthood. The codependency addict continues to live oblivious or in denial of their illness, continuously repeating the behaviors that will eventually lead to him or her to ruin.

Was the source of Delores’ illness her mother’s abandonment at an early age? Or was the illness triggered by George’s having a second family with

Camille Campbell, a fellow student at Bluefield State who lived in Columbus?

Did Myrtle have a codependent addiction because of her forced sterilization by her mother Janie? What caused Janie to tramautize her daughter by cutting off her reproductive choices?

Codependency, according to writer Pia Melody, author of

Facing Codependence, is hereditary. In the succeeding years I discovered that my mother’s defining childhood abuse was an abandonment by her mother at aged three. Her mother’s "illness" was defined by a forced sterilization by her mother, after her sixteen year old childbirth. My great-grandmother was a preacher’s wife and evidently moved to over-control her young daughter’s life by the morals of the day. God only knows if the slave experience that abused the life of my great-grandmother’s ancestors was the tree that roots several generations of codependency and addictions.

Questions that because of death will never be answered. I hope that the codependent addictions have ended with me, but I cannot tell. I can just tell Delores’ story as completly as possible.

Delores Grettavon Williams Howard lived just a little over thirty years. She loved school, like her father remembered, spent too short a time at Bluefield State, because of her pregnancy. But as Mary Liggins-Goodrich recalled, “She was a fantastic scholar.”